Many parents have likely come across this scenario: you reach into your kid’s pockets before putting their clothes in the wash, only to discover that they are filled with rocks. Your first instinct might be to throw those rocks away, but what if instead, you let your child keep those rocks? It turns out that the simple act of allowing a child to collect rocks (and other objects of natural history) may lead to a lifelong appreciation for science—and maybe even a career in science!

From Pocketsful of Rocks to a Passion

After many pocketsful of rocks, my journey to becoming a mineralogist began when I was 6 years old and my father took me to our local geology museum. Seeing the museum-quality versions of minerals in their exquisite forms and colors captured me. Luckily, both of my parents encouraged this interest and soon enough I was collecting small crystals, visiting our local Rock Shop, and joining the local Gem and Mineral Club. This world became truly special to me, not only because I was learning more about minerals, but because the people in those spheres were so encouraging and showed me that there was more to this hobby than just collecting. Asking questions about mineral colors and crystal shapes introduced me to chemistry and physics. Appreciating sparkly, colorful gemstones made me appreciate beauty and art and how minerals are transformed into gemstones by artists called lapidaries. Drawing tiny catalog numbers on my specimens and logging them into excel taught me dexterity and organizational/computer skills.

Finally, as I got older, my dad put me in charge of financial planning and navigation (using paper maps!) for our 6,000+-mile road trips to mines across the Western U.S., both of which proved to be useful life skills. This passion found its way into my college essays and eventually led me to a doctorate in mineralogy and geochemistry. In short, what started out as a curiosity-based hobby became a foundation for my life. Today, I am living my childhood dream career as a research mineralogist and the Coralyn Whitney Curator of Gems and Minerals at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) and one of the most important parts of my job is to encourage the next generation of mineralogists.

G. Farfan

Nurturing Your Kids’ Interest in Geology

If you are a parent reading this, congratulations – your child ROCKS (pun intended)! Here are some tips on how to grow their interest in geology.

-

Visit Museums

All of the reading in the world cannot replace the experience of actually seeing amazing minerals, gems and rocks in person. If you are in the DMV area, you are exceptionally lucky. The Smithsonian NMNH is free and hosts one of the largest and finest mineral and gem collections in the world. Even if you have visited us before, we welcome you back to discover new details (and new specimens) in our exhibit. I encourage you to take notice of the specimen labels in our mineral hall, which include each mineral’s chemical formula – a subtle reminder that minerals are chemical compounds and that there is a hefty amount of science backing their glitz and glam.If you can’t come in person, the NMNH offers a virtual tour, as well as our GeoGallery. I also encourage all to visit other local natural history museums. As a mineral scientist and curator, I am part of a network of mineral curators around the globe that work at museums big and small. Each has something special to offer. My experience at the small but mighty UW Madison Geology Museum was life-changing.

- Read books and credible online resources For younger children, I would recommend starting with a lighter handbook that is picture-heavy. The Gemological Institute (GIA) has developed a website called GemKids that is an excellent resource for getting started and it has a link for book recommendations. For grades 3-5, the NMNH website is full of videos and lessons designed to align with school standards, such as the “Science How” archived webinars and videos on the NMNH YouTube Channel. As your child gets older, they may pick up more specialized texts in mineralogy and turn to credible online sources, such as the popular MinDat. Finally, the most accurate account of the Hope Diamond story can be found on our NMNH website and in the latest book on the National Gem Collection titled Unearthed, Surprising Stories Behind the Jewels.

-

Become a part of your local gem/mineral/rock community

Being a “rock hound” (someone who collects minerals, gems and rocks) can take many forms. Some people enjoy building mineral and gem collections, others like to cut rocks (lapidary) and lean into the artistry aspects of the hobby and others like to go out into the field and hunt for stones themselves. These interests may often overlap at a local gem and mineral club or local “rock shop.” There are mineralogy societies in D.C., Maryland and Northern Virginia, all of which are encouraging of young members. These clubs are also the best resources for recommendations on local rockhounding. -

Go Rockhounding

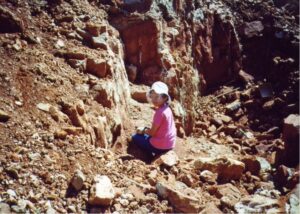

Collecting minerals in the mud is the best way to engage with nature and have the joy of being the first human to see a stone come out of the ground. Alternatively, if you do not find anything, there is an important lesson there in patience and expectations. During my first rockhounding trip to Crater of Diamonds State Park in Arkansas, I did not find a single diamond, still, I remember having fun digging and hoping I would find one.Local mineral clubs may have field trips to sites that would otherwise be closed to the public. There are also established mines across the country that are open to “fee digging” for collecting. Some of my collecting highlights would include diamonds and quartz in Arkansas, sapphires (corundum) in Montana, Oregon sunstones (labradorite) in Oregon and opals in Nevada. Just remember, when mining, always safety first!

Wishing you and your kid(s) the best in your mineralogy adventures!

Gabriela A. Farfan, Ph.D. is Coralyn Whitney Curator of Gems and Minerals, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History. She has a Ph.D. from Massachusetts Institute of Technology/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and a Bachelor of Science from Stanford University.